Chicano Park is a 32,000 square

meter (7.9 acre) park located beneath the San Diego-Coronado Bridge in Barrio

Logan, a predominantly Mexican American and Mexican-immigrant community in

central San Diego, California.

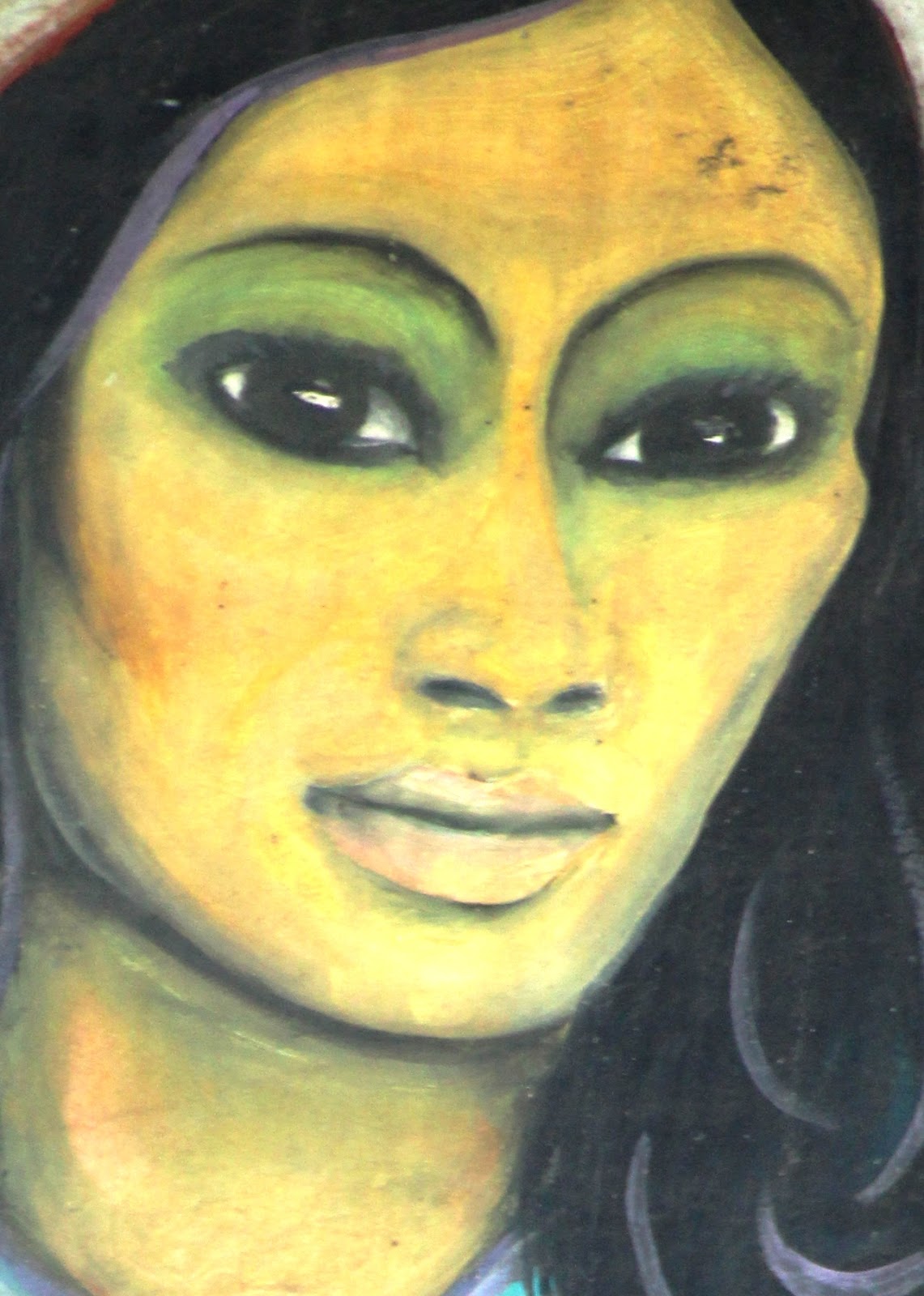

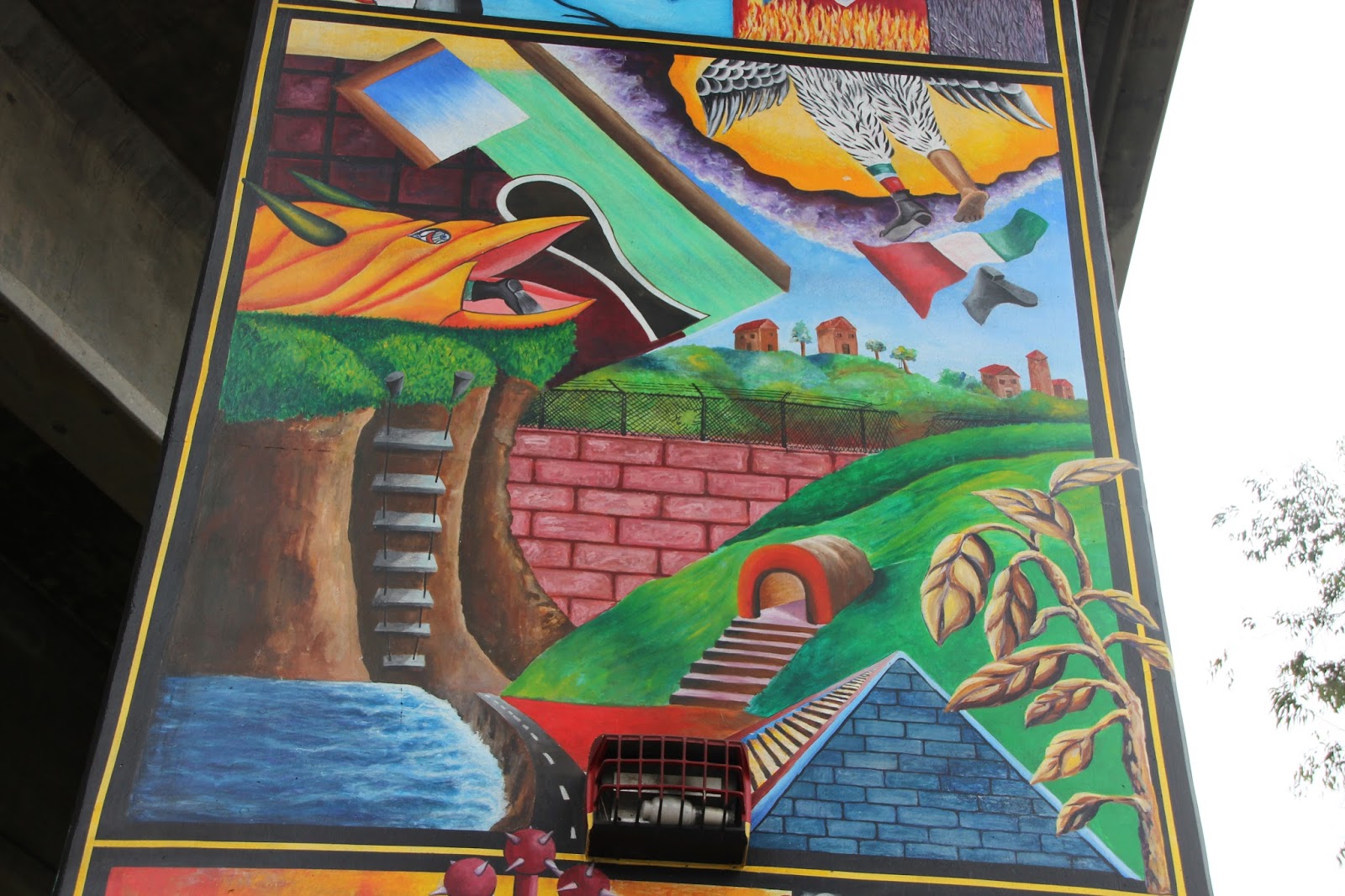

The park is home to the country's largest

collection of outdoor murals as well as various sculptures, earthworks, and an

architectural piece dedicated to the cultural heritage of the community. For

the magnitude and historical significance of the murals, the park was

designated an official historic site by the San Diego Historical Site Board in

1980, and its murals were officially recognized as public art by the San Diego

Public Advisory Board in 1987.

The park was listed on the National Register

of Historic Places listings in San Diego County, California in January 2013

owing to its association with the Chicano civil rights movement. Chicano Park,

like Berkeley's People's Park, was the result of a militant (but nonviolent)

people's land takeover. Every year on April 22 (or the nearest Saturday), the

community celebrates the anniversary of the park's takeover with a celebration

called Chicano Park Day.

The area was originally known

as the East End, but was renamed Logan Heights in 1905. The first Mexican

settlers there arrived in the 1890s, followed soon after by refugees fleeing

the violence of the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910. So many Mexican

immigrants and Mexican-Americans settled there that the southern portion of

Logan Heights eventually became known as Barrio Logan.

The original neighborhood

reached all the way to San Diego Bay, with waterfront access for the residents.

This access was denied beginning with World War II, when Naval installations

blocked local access to the beach. The denial of beachfront access was the

initial source of the community's resentment of the government and its

agencies.

This resentment grew in the

1950s, when the area was rezoned as mixed residential and industrial. Junk

dealers and repair shops moved into the barrio, creating air pollution, loud

noise, and aesthetic conditions unsuitable for a residential area. Resentment

continued to grow as the barrio was cleaved in two by Interstate 5 in 1963 and

was further divided in 1969 by the elevated onramps of the San Diego-Coronado

Bridge.

At this time, Mexicans were

accustomed to not being included in discussions concerning their communities

and to not being represented by their officials, so no formal complaint was

lodged.

This attitude began to change

in the turbulent decade that brought the demands of African Americans, women,

and other oppressed peoples for equality and full inclusion in American

society.

As the various campaigns

coalesced under the banner of the Chicano Movement (for the right to organize

and collectively bargain, led by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta of the United

Farm Workers, the rights to the full benefits guaranteed to veterans, led by

Dr. Hector P. Garcia of the American G.I. Forum, the right to equal and

pertinent education, led by the student group MEChA which issued the Plan de

Santa Barbara, for the rights of Mexicans guaranteed under the Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo, (especially land grants and bilingual education) under Reies Tijerina,

and for recognition of the historic contributions of Mexican-Americans and the

validity of Mexican culture) so too did the political awareness and sense of

empowerment grow in Barrio Logan.

Community residents had long

been demanding a park. The City Council had promised to build a park to

compensate for the loss of over 5,000 homes and businesses removed for the

construction of the freeway and bridge, as well as for the aesthetic

degradation created by the overhead freeways supported by a forest of gray

concrete piers. In June 1969, the park was officially approved and a site was

designated, but no action was taken to implement the decision.

The final straw came on April

22, 1970. On his way to school, a community member, San Diego City College

student, and Brown Beret member named Mario Solis noticed bulldozers next to

the area designated for the park. When he inquired about the nature of the work

being undertaken, he was shocked to discover that, rather than a park, the crew

was preparing to build a parking lot next to a building that would be converted

into a California Highway Patrol station.

Solis went door-to-door to

spread the news of the construction. At school, he alerted the students of

Professor Gil Robledo's Chicano studies class, who printed fliers to bring more

attention to the affair. At noon that day, Mexican-American high school

students walked out of their classes to join other neighbors who had already

congregated at the site.

Some protesters formed human

chains around the bulldozers, while others planted trees, flowers, and cactus.

Solis is reported to have commandeered a bulldozer to flatten the land for

planting. Also, notably, the flag of Aztlán was raised on an old telephone

pole, marking a symbolic 'reclamation' of land that was once Mexico by people

of Mexican descent.

When the crowd grew to 250,

construction was called off. The occupation of Chicano Park lasted for twelve

days while community members and city officials held meetings to negotiate the

creation of a park. During that time, groups of people came from Los Angeles

and Santa Barbara to join the occupation and express solidarity.

Not trusting the city and fearing that

abandoning the land would be tantamount to conceding defeat, an agreement was

finally reached whereby the recently formed Chicano Park Steering Committee

would call for an end to the occupation of the land while stationing informal

picketers on the public sidewalks around the disputed terrain to provide

residents with information regarding the project. They maintained that the park

would be re-occupied if negotiations failed.

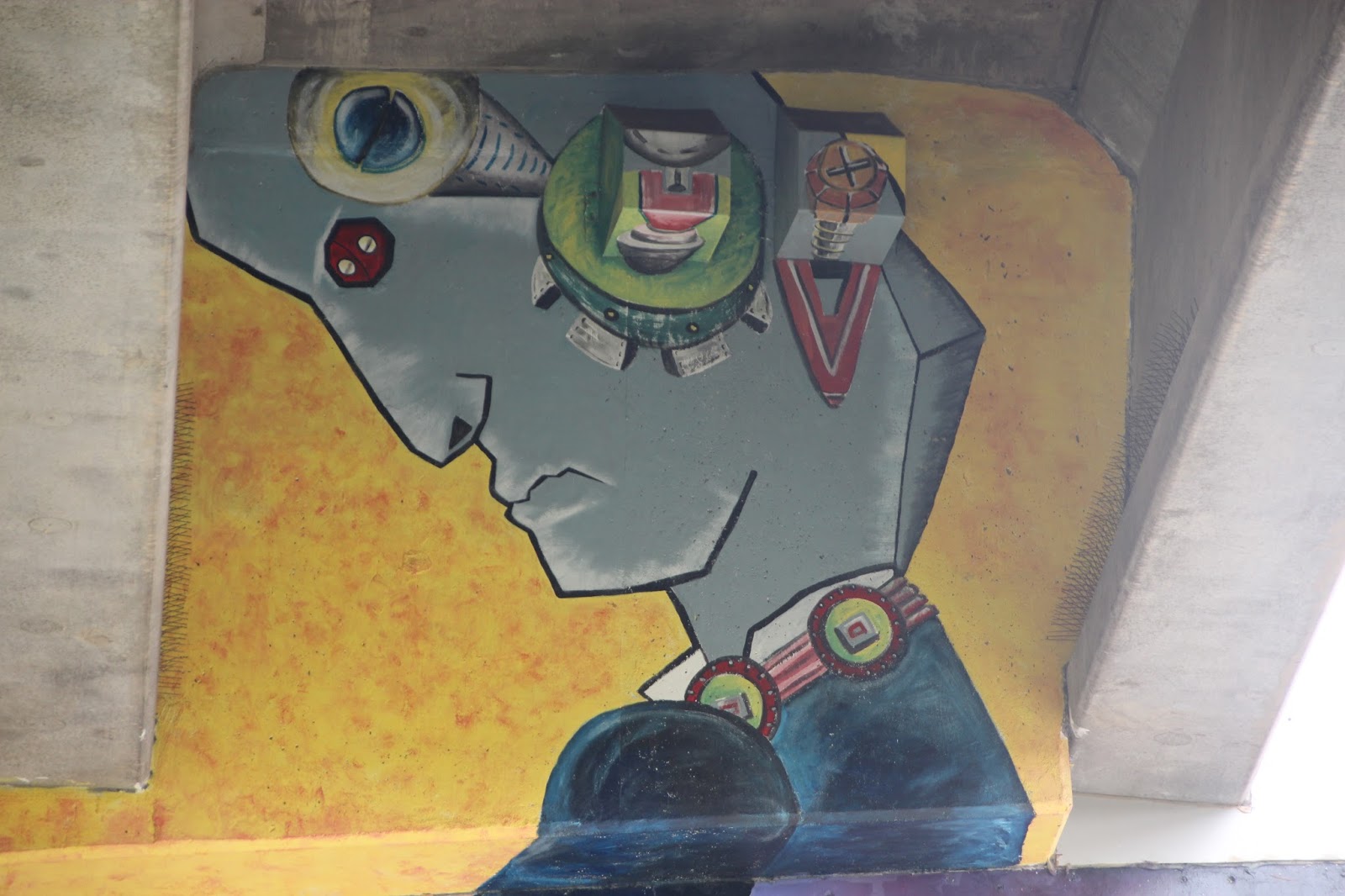

At a meeting on April 23, a

young artist named Salvador Torres, recently returned to the barrio from the

College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, shared his vision of adorning the

freeway support pillars with beautiful artworks. For this reason, he is

sometimes referred to as "the architect of the dream". Finally, on

July 1, 1970, $21,814.96 was allocated for the development of a 1.8 acre (7,300

m²) parcel of land.

While the creation of the park

was actually begun on the day of the takeover, with minor landscaping improvements

being undertaken by the occupiers, the murals that brought the park to

prominence were not begun until 1973.

With few exceptions, the

artists and their organizations raised the money necessary to purchase muriatic

acid to wash the columns, rubber surface conditioner to prepare them, and

paints.

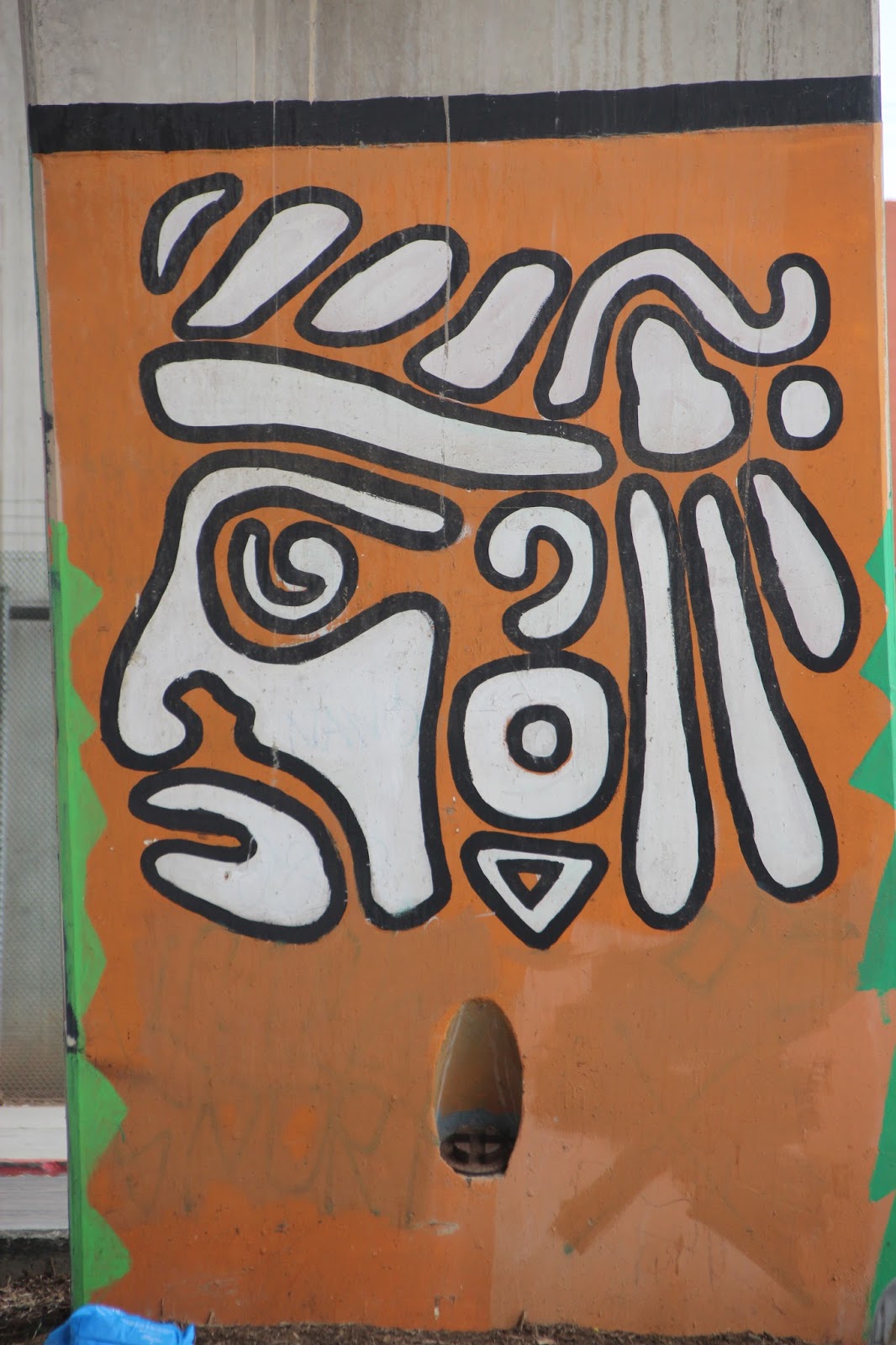

Artists were invited from all

over the state, with notable contributions from the Royal Chicano Air Force of

Sacramento and the mural team of Charles "Gato" Félix, responsible

for the murals at the Estrada Courts in Los Angeles. Many non-Chicanos also

participated. Over time, more vegetation was planted to create a cactus garden.

Other additions to the park

have been piecemeal, as the comprehensive "Master Plan" put forth by

the artists was never adopted by the city. The park has expanded, and currently

reaches almost "all the way to the bay", a phrase used as the rally

cry to extend the park in a 1980 campaign.

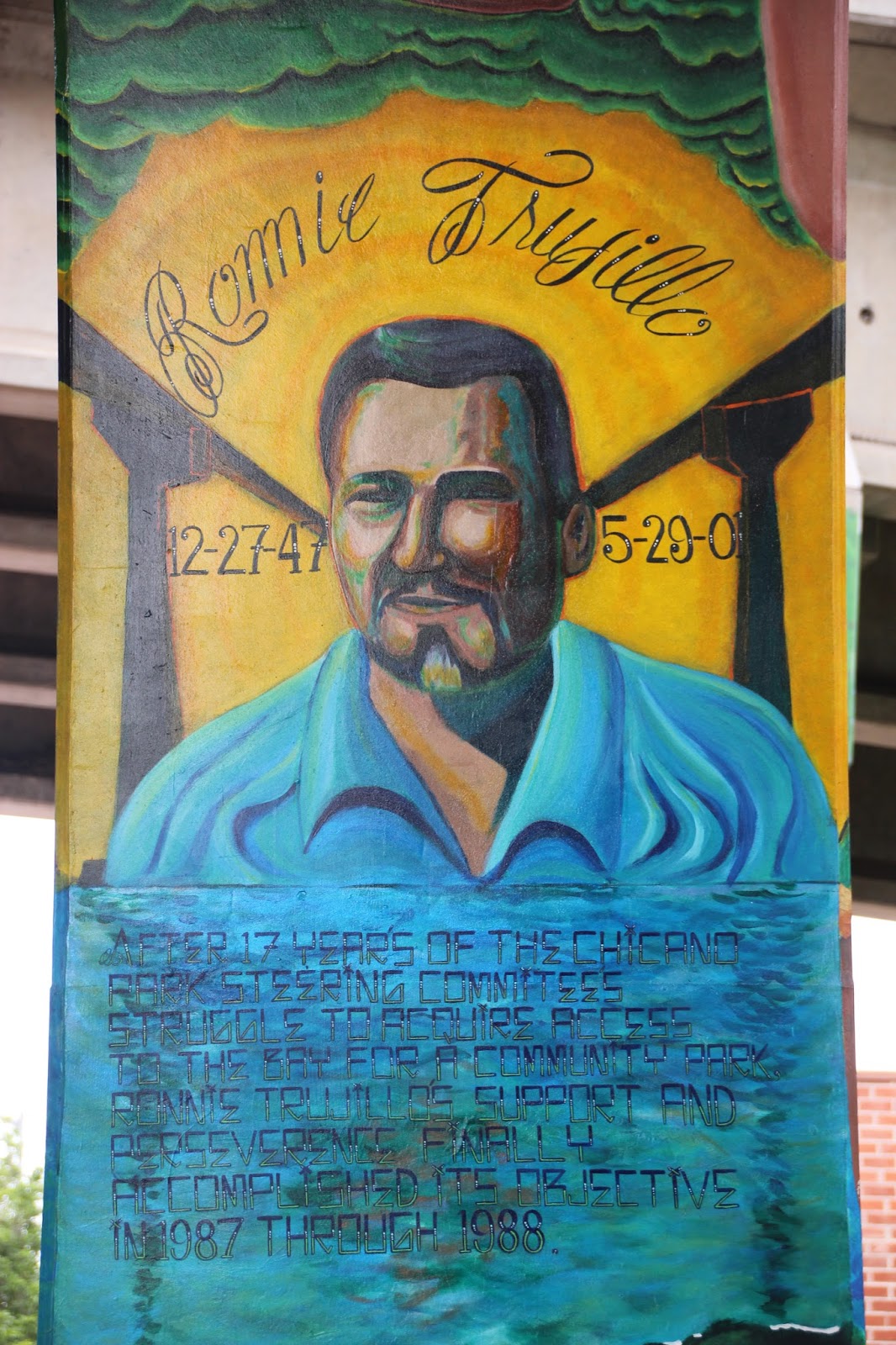

The Cesar E. Chávez Waterfront

Park was begun in 1987 and completed in 1990, finally restoring beach access to

the community. With the exception of three city blocks that are not part of the

park, the original goal of creating a community park with waterfront access has

been achieved. Major mural restoration projects began in 1984, and the murals

have been restored almost continuously ever since.

Since its inception, Chicano

Park has been a source of controversy. There have been disputes within the

community about who decides who gets to paint the murals, what imagery should

be represented, who is responsible for the restoration of the murals, etc. But

conflicts between the community artists and city and state officials have been

much greater. Conflicts have also arisen between defenders of the park and

neighboring Anglo-American communities.

In 1979, a San Diego Grand jury

investigation forced the Chicano Federation to vacate the park building.

A demand for a kiosk, called

the Chicano Park kiosko and based on traditional community centers in Mexican

villages, was fulfilled in 1977, but only after a great deal of bureaucratic

wrangling and disputes over the style of architecture to be used. Councilman

Jess Haro wanted the architecture to be in the Spanish style, while the barrio

residents wanted an indigenous style of architecture. The community won out,

and today the kiosko resembles a Mayan temple.

Barrios Sí, Yonkes No. An

effort to have the barrio re-zoned as (only) residential provoked the ire of

the neighborhood junk dealers, who vandalized the murals, especially the

"Barrio Sí, Yonkes No" mural [yonkes=junkyards] created to

commemorate the effort.

In the mid-1990s, Caltrans

decided to retrofit the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge to make it earthquake

safe. Fearing that the murals would be damaged or destroyed, the community

mobilized to stop the project to protect the murals from what they viewed as

official insensitivity to the history and culture the murals represented.

Eventually, a compromise was reached whereby the murals would be boarded over

with plywood to protect their surfaces from damage during the retrofitting

process, and would be restored to their previous condition afterward.

A 2003 plan to renovate the

park was stalled when Caltrans objected to the word "Aztlán", which

for years had been spelled out in rocks on the park's grounds. Calling the term

"militant", they claimed that using federal funding for the project

would violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by showing preference to

Mexicans and Mexican Americans. However, Caltrans district director Pedro Orso,

after consultations with civil rights experts from within the agency and from

the Federal Highway Administration, decided that the word did not violate the

law, and the $600,000 grant was allowed to go through.

There are communist motifs

scattered throughout several of the murals, including portraits of Fidel Castro

and Che Guevara, and references to Salvador Allende, and Ho Chi Minh (as tío

Ho, a take on his Vietnamese nickname, Bác Hồ which

means "Uncle Ho").