Faig Ahmed

David Hockney on Vincent van Gogh | FULL INTERVIEW

The Forged ‘Ancient’ Statues That Fooled the Met’s Art Experts for Decades

The fakes were on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for 28 years.

BY NATALIE ZARRELLI

The curator who acquired them, John Marshal, wrote “I can find

nothing approaching it in importance,” in a report for the museum; these pieces

challenged known history of ancient Italian art. They were in amazing

condition.

There was just one problem: they were fakes. And for the 28

years they were on proud display, even skeptical experts couldn’t help the Met

evade one of the most embarrassing scandals of the art world.

Marshal and his colleagues at the museum acquired the statues

one-by-one from an artifact dealer named Pietro Stettiner between 1915 and

1921, believing that they were exquisite and unusual examples of Etruscan art

that was more influenced by ancient Greek statues than usual in size and

aesthetic—the shapes of the eyes, mouths, and general features. The statues

were convincing: weathered and cracked, the old warrior statue was missing a

finger and an arm; their striking black glazes seemed just like those of other

ancient works. While acquiring one of the warriors, Marshal’s college wrote

with glee about the artifact’s “wonderful preservation” and added that the

asking price was “quite fantastic.” It all seemed too good to be true—which,

unfortunately for the Met, it was.

According to the New York Times’ article on the forgeries in

February, 1962, the museum had been “uneasy for years” about the large

sculptures. The Etruscan culture influenced and invented much of what we think

of as Roman, and there were plenty of scholars studying the society’s art;

Italian historians in particular began voicing their concerns before the

sculptures were displayed. After Marshal’s death in 1928, more rumors

circulated about Stettiner’s supposed excavators of the pieces, who were linked

to other forgeries in Italy.

While the Met’s 1933 Bulletin insisted that the warriors had

been “compared with vigor” and they seemed to compare with other Etruscan works

from the fifth century, critics concluded that the sculptures seemed a bit out

of place; they were the wrong shape and size. The statues were amazingly

complete and well-preserved for their age, yet the old warrior was missing a

whole arm. The big warrior was weirdly proportioned, with one oddly long arm

and a stocky frame on classically formed legs. According to some experts, they

weren’t even particularly good examples of Etruscan artwork. More concerns

fluttered into the museum as its exhibit descriptions crept around Europe.

Over the years of the exhibit, the museum’s experts explained

this and other doubts away, possibly because of the pure high of new discovery

and an attitude in the Western art world that assumed superiority and beauty of

classical art. In 1921 art historian and authority Gisela Richter seemingly got

carried away in the museum’s Papers on the Etruscan warriors; the find agreed

with the exquisite descriptions of Etruscan art in historical writings. “Whom

did our warrior represent? Was he a god or a mortal?” she wondered. Richter

regretted that her colleagues didn’t know its original location, but believed

it might have represented a god—the edge of an altar base seemed to be

preserved. Other historians agreed, and examined the statues with wonder.

Weirdly, while the statues’ flaws evaded Richter and others,

museum staff examined the pieces closely enough to know specific details,

including that the large warrior was “built free hand from the bottom up.”

Richter’s paper had also explained that the statues were “Under Greek influence

but Italian in nature,” which became a popular deflecting argument in years to

come. This last bit, at least, was technically correct, but the Italians who

made it were much more modern than expected.

In Italy in the early 20th century, three brothers Riccardo,

Teodoro, and Virgilio Angelino Riccardi, and their colleague Alfredo Adolfo

Fioravanti were living an archeological forger’s dream: they had easy access to

actual artifacts, and both legitimate and corrupt antique dealers who wanted

repairs and copies made of their wares. According to George Kohn in The New

Encyclopedia of American Scandal, the forgers were long suspected to have made

unauthorized excavations in Italy by the government, but managed to avoid

actual prosecution. In their studio, the forgers sculpted the large warriors

and painted them black, broke them up to fire the sections in their small kiln,

and then sent the pieces to their artifact dealer covered with a smattering of

mud.

For decades, experts murmured back and forth about the

authenticity of the statues, but they lacked evidence to discredit them.

Finally, in 1960, ceramic archaeologist Joseph V. Noble of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art found a way to test the sculptures: by replicating the methods

that the ancient Etruscans used for pottery, he found they used a three stage

firing process to make the black glaze and ordered tests of the pottery’s

chemical makeup that revealed a black pigment containing manganese, which

Etruscans did not use. Noble and a colleague published the exposé, which

included tests, researched documents and letters as proof.

There were other red flags that could have been seen earlier on,

too. Authentic pieces should have had vent holes to let air circulate through

the large ceramic pieces if they had been made and fired whole, but small vent

holes were found in two of the statues; the old warrior, which had none, would

have exploded had it been made the correct way. In 1961, the surviving forger

of the group, Fioravanti, was finally persuaded by museum investigators to

appear before the U.S. consulate in Rome to confess the crime holding the left

thumb of the big warrior, which he’d kept as a souvenir, according to the New

York Times’ description of the events.

The big reveal of the sculptures’ inauthenticity paired with

their long-term display was about as scandalous as it could get for a highly

esteemed art institution. The forgers had copied the big warrior from a picture

of a small bronze Greek statue in a book from the Berlin Museum; the old

warrior from an Etruscan coffin at the British Museum, which Kohn writes also

turned out to be fake. Most embarrassing of all, the large warrior head was

modeled from a head found on a small Etruscan vase in the Met’s own collection.

The weird proportions of the big warrior were, it turned out, the result of a

short ceiling and small studio. The arm was missing from the large warrior

because, as Kohn writes, Fioravanti and the Riccardi brothers couldn’t agree on

which way to attach the original arm.

According to the Times in 1962, after the sculptures were outed

as fakes, they were locked up in a “morgue” in the basement with restricted

viewing for students and scholars, never to be fawned over again. But, for a

time, the clumsy art of some Italian potters made experts point in awe—leading

to the first time the Met would ever admit to forgeries in an esteemed

collection (though, thanks to Noble, not the last). While detecting forgeries

is tricky, one thing is certain: if the authenticity of a piece of art is

important to you, it pays to be careful.

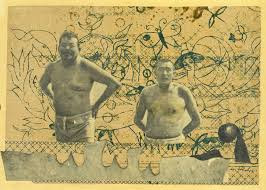

Full Fathom Five

Full Fathom Five is one of Pollock’s earliest “drip” paintings. While its lacelike top layers consist of poured skeins of house paint, Pollock built up the underlayer using a brush and palette knife. A close look reveals an assortment of objects embedded in the surface, including cigarette butts, nails, thumbtacks, buttons, coins, and a key. Though many of these items are obscured by paint, they contribute to the work’s dense and encrusted appearance. The title, suggested by a neighbor, comes from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, in which the character Ariel describes a death by shipwreck: “Full fathom five thy father lies / Of his bones are coral made / Those are pearls that were his eyes.”

How Mafia Money Helps Drive The Global Art Market

How Mafia Money Helps Drive The Global Art Market

"The global art market is

worth between 58 and 60 billion euros." -

Valuable pieces of art have a

special appeal to people in organized crime, both as trophies — conveying power

and prestige — and as a means to launder ill-gained earnings.

Maria Berlinguer

LA STAMPA

ROME — Gioacchino Campolo,

Italy's video poker king, loved art. Among the 300 million euros worth of goods

confiscated from him were about 100 very valuable works of art: paintings by

Salvador Dali, Giorgio Morandi, Renato Guttuso, Mattia Petri, and Giorgio de

Chirico.

Collections in the tens of

millions of euros were also confiscated from: Nicola Schiavone, son of Franceso

Schiavone, boss of the Casalesi clan within the Naples-based Camorra crime

syndicate; and from Gianfranco Becchina, art dealer to Matteo Messina Denaro,

boss of Sicily's Cosa Nostra.

Let's not, of course, forget the

two Van Gogh oil paintings — Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church at Nuenen

and View of the Sea at Scheveningen — which were stolen in 2002 from the Van

Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and later found by Italian financial crime unit

officers in Castellamare di Stabia, Naples, in a cottage linked to drug

trafficking kingpin Raffaele Imperiale.

And then there are the

'Ndrangheta investments in 17th-Century paintings in Lombardy, and the

collections of Gennaro Mokbel and Massimo Carminati, active figures on the

piazza of Rome, at the center of the must-see documentary Follow the Paintings

by Francesca Sironi, Alberto Gottardo and Paolo Fantauzzi.

Are criminals and mafia bosses

really this passionate about art? Hard to imagine. More likely it's a sign of

just how much the art market has become a phenomenal money laundering and

investment tool for organized crime. It's a sector that allows dirty money to

be hidden, safe and sound, with a guaranteed protection against devaluation

over time.

And this isn't just about

laundering. Artwork offers the certainty of an investment that won't have

inflationary repercussions, and with a guaranteed return to boot, provided the

money is invested in masterpieces destined to securely maintain their value

over time.

The global art market is worth

between 58 and 60 billion euros. It's a worldwide boom that doubled in size in

the last 10 years, and which shows no sign of imploding. And not just thanks to

those evergreen works, the masterpieces. It's also due to the exponential rise

in prices for works by skyrocketing young artists, pieces that can in some

cases top $100 million. All anomalies, according to experts in the sector.

In the past decade, galleries and

auction houses have beat record after record, succeeding in placing both

masterpieces and works by artists launched from semi-anonymity to worldwide

commercial success.

It's a sector that has benefited from an

absolute lack of regulation.

But not all that glitters is gold, because

passionate collectors aren't the only ones driving the market's wild expansion.

Also fueling the frenzy is the ease with which mob interests have so far been

able to use this commercial bubble to recycle illicit funds. We're talking

about a sector, in other words, that has benefited from an absolute lack of

regulation.

"It's a flow of cash coming

above all from the drug trade," explains Gen. Allesandro Barbera,

commander of Scico, the central investigative service on organized crime of the

Guardia di Finanza.

Roughly 18 billion euros (or 1%

of Italy's GDP) is the colossal value of real estate and goods confiscated by

the Italian financial authorities from criminals between 2015 and 2019.

Seizures that confirm the importance of what is seen as a strategic choice of

the mob to invest in safe-haven assets: principally diamonds, precious metals,

paintings and archeological finds.

These treasures aren't all

stolen. Many are acquired legally on the art market, above all at auction.

"The mafia enterprise moves

indiscriminately between the two words, legal and illegal, which makes it

particularly tricky," Barbera explains. "For the clans, safe-haven

assets like works of art are desirable because they are convenient. It's a business

with branches all over the world, very difficult to reconstruct. We find

ourselves constantly facing a two-faced Janus, and it requires ever more

sophisticated investigative techniques to find where the illicit funds are

hiding, and to map out all the money transfers."

Barbera adds: "When you find

yourself facing a mafia organization that moves in the legal art market, you

don't need sharpshooters so much as business-minded investigators who know how

to read financial statements."

Works of art and safe-haven

assets, he explains, are today's "cashier's checks: exchange goods with

stable value and a double advantage — masking the provenance of the

investments, and guaranteeing the availability of the good in real time on the

global market."

They are like trophies to exhibit as

demonstrations of power.

The criminal chain operates, furthermore, like

a value chain that, in its various phases, succeeds in raising and sustaining a

constant growth in value.

Investigators have also succeeded

in documenting a "reverb effect" enjoyed by the chief clans that own

artistic masterpieces with universally recognized value. The extremely coveted

items are trophies to exhibit as public demonstrations of power, prestige and

dominion over their territory.

"For a mafia boss, having a

painting or a sculpture by a major artist at his disposal is not just a

money-laundering scheme. Being able to exhibit a masterpiece confers prestige

and reputation," the general says. "It contributes to spreading the

idea of supremacy that a hegemonic group wants to express in a geographic area,

or an in a specific sector of illicit traffic."

Thus the possession of art

becomes a sign of power and socio-cultural investiture. A status symbol. It's a

well-oiled machine. Over the years, the clans have perfected the methods of

hiding money trails coming from drugs and various other rackets and trades.

"Organized crime, in its

different expressions, have an interest in investing in goods that can help

hide their net worth," says Federico Cafiero De Raho. "Works of art

with astronomical values are thus used as instruments to safely deposit huge

sums of wealth."

And with a specific advantage for

clans. "These investments in paintings, sculptures and archeological

treasures effectively cover up the economic entity concentrated in the

object," he adds.

A way, then, to muddy the waters,

to not give any certainty as to how much illegal money has been laundered along

the successive gears of the "artistic laundry machine." The price of

an artwork remains secret. To determine how valuable it is, one must turn to a

market that is based on subjective valuations.

The national anti-mafia

prosecutor reconstructs a constantly updated case study that points

unequivocally to a method of hidden payment via art. In hundreds of cases, in

fact, paintings, sculptures and frescoes guarantee money transfers from one

mafia group to another, protected from any risk.

With a piece of paper, with a

private agreement, an exchange of virtual currency is implemented and secured

between criminal organizations without a single masterpiece, and in some cases

even entire art galleries, needing to be transferred from one location to

another.

The artwork remains where it is

kept — perhaps in a free port or duty-free zone, inaccessible to all — and

passes from one buyer to another.

And this is one of the new

frontiers on which attention is being focused, by investigators and

legislators. Meanwhile, the fifth directive of the European Union on anti-money

laundering imposes on art sector operators the same regulations of transparency

currently applicable to banks, notaries and accountants.

Houses of Parliament

Houses of Parliament,

London, Claude Monet, 1900, Art Institute of Chicago: European Painting and

Sculpture. During his London campaigns, Claude Monet painted the Houses of

Parliament in the late afternoon and at sunset from a terrace at Saint Thomas’s

Hospital. This viewpoint was close to that of the English artist J. M. W.

Turner in his visionary paintings of the fire that had destroyed much of the

old Parliament complex in 1834. In his response to the poetry of dusk and mist,

however, Monet was actually inspired by the work of a more recent painter of

the Thames, the American James McNeill Whistler.