By Robin Pogrebin and Scott Reyburn

May 14, 2018

At this point in the art market, it’s hard not to get inured to the superlatives: the most valuable private collection sold at auction (the Rockefeller sale last week at Christie’s); the highest price ever paid for a painting ($450 million for Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” in November at Christie’s) and what Sotheby’s had confirmed was the highest estimate ever placed on a work at auction ($150 million for Amedeo Modigliani’s 1917 painting, “Nu Couché (Sur Le Côté Gauche).”

The Modigliani barely made it past that figure Monday evening at Sotheby’s, selling for $157.2 million with fees at a sale that otherwise featured what many agreed were B+ offerings.

“You cannot find any more masterpieces,” said the dealer David Nahmad, adding of Sotheby’s, “Considering what they had, they did well.”

Although it was the highest auction price ever for a work sold at Sotheby’s, equally noteworthy is that the painting also carried the highest guarantee ever given by the company. This meant that the auction house was willing to assure a minimum price to the owner, potentially risking millions. Sotheby’s was able to offload that risk to a third party, who became the buyer at the auction.

The scale of the guarantee confirms that buyers can be secured in advance for trophy works. The results on Monday, the first night of the spring auctions, seemed to bear that out — although the Modigliani sold on one bid to the third party without any other buyer interest (despite valiant efforts by the auctioneer, Helena Newman, to bring in Patti Wong, the chairwoman of Sotheby’s Asia, who was working the phones).

Image

“It cleared the mark painfully,” said Christian Ogier, a Paris dealer in Impressionist and modern art. “It’s difficult to get money out of China at the moment,” he added, referring to the absence of bidding on the Modigliani from Ms. Wong. “Everyone knew what was expected. The high guarantees break the dynamics of an auction, somehow.”

The overall atmosphere in the salesroom on Monday evening was muted, with few lots selling above their high estimates at a pace that, at times, felt glacial; 13 lots failed to sell. The only applause of the night was when the hammer came down on Jean Arp’s curvilinear sculpture “Ptolémée II” for $2.2 million with fees, selling to the dealer Eykyn Maclean in the room.

And the price of the Modigliani fell short of the last auction high for a work by the Italian modernist: $170.4 million for the more overtly sensual 1917-18 canvas, “Nu Couché,” which in 2015 sold at Christie’s to Liu Yiqian, a former taxi driver turned billionaire art collector.

Still, the $100 million club keeps adding more members, including Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose untitled painting sold for $110.5 million last year; Pablo Picasso, whose “Women of Algiers” sold for $179.4 million in 2015; and Andy Warhol, whose car crash painting sold for $105.4 million in 2013.

The Modigliani for sale on Monday was one of a celebrated series of nudes commissioned from by his Paris dealer Léopold Zborowski (for a stipend of 15 francs per day). The painting was consigned to Sotheby’s by the billionaire Irish horse breeder and art collector John Magnier, who had bought the work at auction in 2003 for $26.9 million, which at the time was a high for the artist.

The seller sought to capitalize on the painting’s recent inclusion in theModigliani retrospective that closed last month at Tate Modern in London, where it was featured on posters and on the cover of the catalog.

If a lot sells for the guarantee, the winning bidder becomes the owner. But if it exceeds the guarantee price, the guarantor earns a percentage of the surplus amount, a quick way to earn potentially millions of dollars. (The identity of the buyer of the Modigliani was not revealed.)

“In order to win the painting, they had to come up with a strong guarantee and a strong deal structure,” said Brett Gorvy, a former Christie’s executive who is now a private dealer, referring to Sotheby’s. “When you look at rest of their sale, it’s very O.K., but nothing exciting.”

“They needed that Modigliani, specifically going up against Rockefeller,” he added, recalling last week’s $833 million auction at Christie’s.

There are many art world professionals who bemoan the increasing trend toward guarantees, arguing that it takes the democratizating suspense out of the auction — only those who can commit large sums in advance can compete (sometimes that is the auction house itself). The result is that the biggest lots have essentially been presold, without publicly available information about the financial terms of each deal.

“What drives some of these huge presale estimates is actually the negotiation that takes place with the prospective third-party guarantor, the sale before the sale,” said David Norman, an art adviser based in New York, who until 2016 was Sotheby’s vice chairman of Sotheby’s Americas and its co-chairman of Impressionist and modern art worldwide. “Basically $100 million is where one has to begin to price a truly great work by any of the major artists.”

Valuation increases of between four- and fivefold also characterized significant works by Claude Monet and Pablo Picasso that had been acquired by their sellers back in the early 2000s.

Monet’s 1896 canvas, “Matinée sur la Seine,” had been bought by an unidentified American collector at auction for $5.7 million in 2000. At Sotheby’s, it was given a low estimate of $18 million and sold for $20.5 million to a telephone bid.

The sale of Picasso’s small 1932 head study of a dreaming Marie-Thérèse Walter, “Le Repos,” was timed to coincide with Tate Modern’s current blockbuster show, “Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy.” The owner had acquired the painting at auction in 2000 for $7.9 million. The painting sold for $36.9 million.

Sotheby’s total of $318.3 million from 45 lots exceeded the $173.8 million total for its Impressionist and modern sale last year, in which no work was valued at more than $30 million.

Before the auction, a cluster of protesters gathered outside the auction house’s York Avenue headquarters, objecting to the inclusion in the sale of works from the Berkshire Museum, in Pittsfield, Mass. In April, a Massachusetts judge ruled that the cash-strapped museum could proceed with its controversial plans to sell a much loved painting by Norman Rockwell and other artworks to fund its redevelopment.

Sotheby’s sale of Impressionist and modern works included works on paper by Francis Picabia and Henry Moore, the first works to be auctioned from the Berkshire Museum’s collection. Picabia’s 1914 abstract “Force comique” brought $1.1 million with fees, and Moore’s 1942 “Three Seated Women,” $300,000. Both works had formerly been owned by Massachusetts collectors.

That the Modigliani failed to generate the excitement Sotheby’s had hoped cast something of a pall over the evening. “There was only one winner — the seller,” said Alan Hobart, the director of the London-based Pyms Gallery, who thought Sotheby’s priced the painting too ambitiously. “They’re testing the market too hard. They have to be careful.”

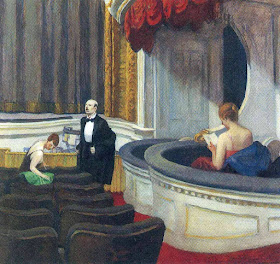

Amedeo Modigliani’s 1917 painting, “Nu Couché (Sur Le Côté Gauche),” which sold for $157.2 million at Sotheby’s

Henry Moore’s “Three Seated Women” (1942), sold for $300,000, with fees, by the financially strapped Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Mass. The long dispute over the proposed sale of dozens of works ended last month with a judge’s decision to allow the sale.CreditSotheby’s

Pablo Picasso's "Le Repos," from 1932, sold at Sotheby's for $36.9 million.Credit2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, via Sotheby’s

Francis Picabia’s “Force Comique” (1914) sold for $1,119,000, also from the Berkshire Museum to benefit the financially strapped institution.CreditSotheby's