Wealthy investors flock to fine art funds

By Sophia Yan

Wealthy

investors looking to diversify beyond stocks and bonds are now turning to an

unusual money-making vehicle -- the art

investment fund.

The name says

it all: These funds invest in fine art and seek returns by acquiring and

selling high-end pieces for profit.

Growth in art

investing has helped smash records for international art sales, which hit $66

billion last year. And the idea has been catching on with the very rich -- a

group that already uses collectors' items and luxury goods as investments -- in

the years following the global financial crisis.

"People

are looking at new areas to invest in, and at the moment art is one of those --

it's making people money," said Jon Reade, co-founder of Hong Kong-based

art brokerage Art Futures Group.

As with stocks,

fund managers might buy pieces they believe are currently undervalued, perhaps

from emerging artists. Funds can also buy into "blue-chip" artists --

similar to blue-chip stocks, these are top artists whose coveted works may

offer more reliable returns.

Some art

investment funds focus on investing in art from a certain region, a particular

style period, or a specific medium, such as photography.

Another

strategy is to buy in bulk, from a gallery or artist nearing bankruptcy, or to

arrange for pieces to be exhibited -- a move that can help increase value.

Fund managers

try to predict when a certain work will peak in value -- the golden moment to

sell for a profit. To accomplish this, managers track a variety of indicators

from auction houses, curators and galleries that can illuminate otherwise murky

trends.

These funds can

carry a hefty price tag -- London's Fine Art Fund Group requires a minimum

investment of $500,000 to $1 million per investor.

"It's a

very significant threshold, so it's not a fund for widows, orphans or retail

investors," said CEO Philip Hoffman. "It's purely for high net worth

and institutional type investors."

Art funds are

relatively new, and hold total assets of roughly $2 billion worldwide,

according to the Art Fund Association, an industry group. That's still tiny

compared to the $2.6 trillion hedge fund industry.

But related

businesses are already springing up to support investing in art, such as

freeports -- highly secure, tax-free places to stash fine art and other luxury

items.

Future demand

for art funds is expected to come from Asia, and especially China. Chinese

demand boosted the global art fund market by 69% in 2012 alone, according to a

Deloitte report.

Art investing

is attractive to the Chinese due to limited investment options in the country.

Plus, it promises big gains -- China's contemporary art market has gained

roughly 15% each year in the last decade, while stocks have been largely flat,

said New York University professor

Jianping Mei, the developer of a fine art index.

Critics say a

lack of regulation and the opaque nature of the market make art one of the

riskiest investment options out there. Some have even accused wealth managers

of exploiting the lack of transparency to bid up certain artists or works in

order to raise the value of their funds.

And art is not

as liquid an investment as assets such as stocks or bonds. Investors should expect

to hold pieces for years, and be prepared to absorb insurance and storage costs

during that time.

But supporters

say these characteristics make art an extraordinary and rewarding investment.

"You get

the benefit of a beautiful work of art you can enjoy on your wall," said

Diana Wierbicki, who specializes in art law at Withers. "It's also an

asset that is appreciating in value, because it's a market that's so

strong."

Art for the Pop of It: Pop art for your feet

Art for the Pop of It: Pop art for your feet: Stuti Agarwal Hand-painted shoes in vivid colours and wow designs are quite the rage among fashionistas. Legend has it that Cindere...

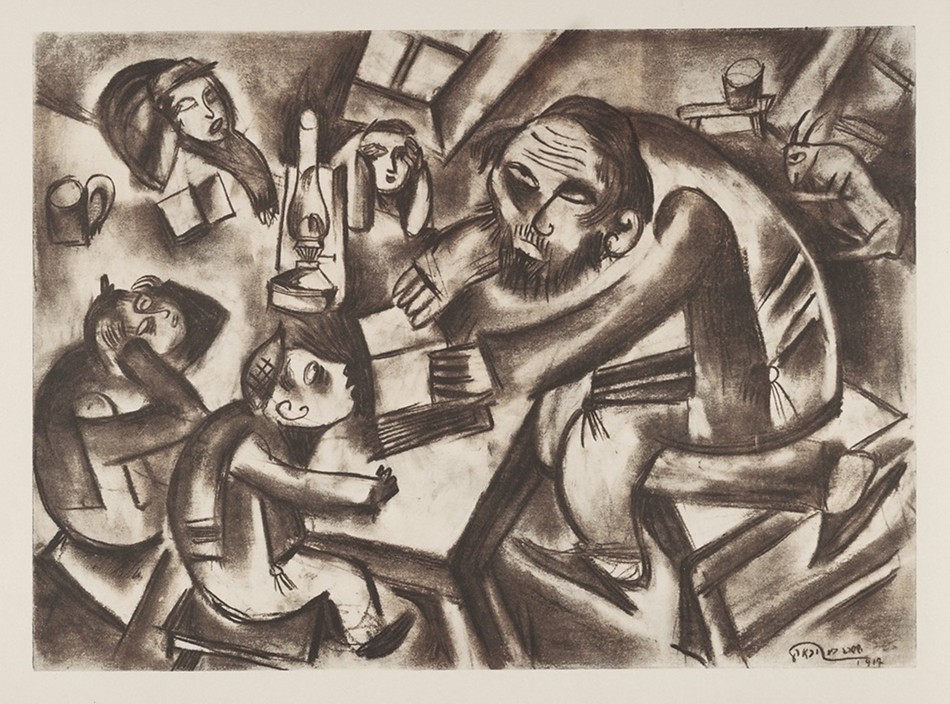

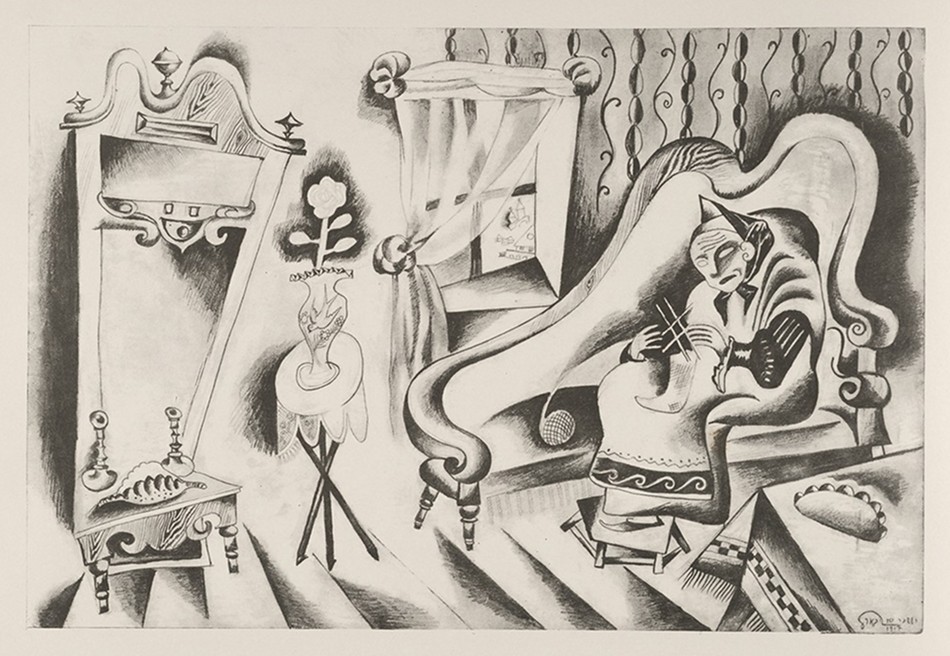

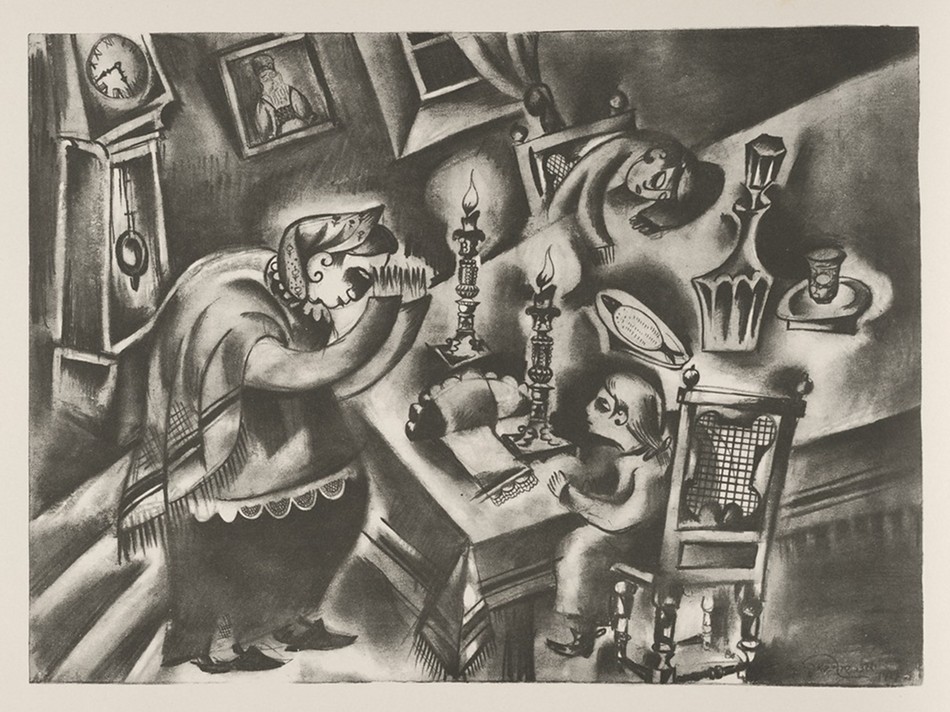

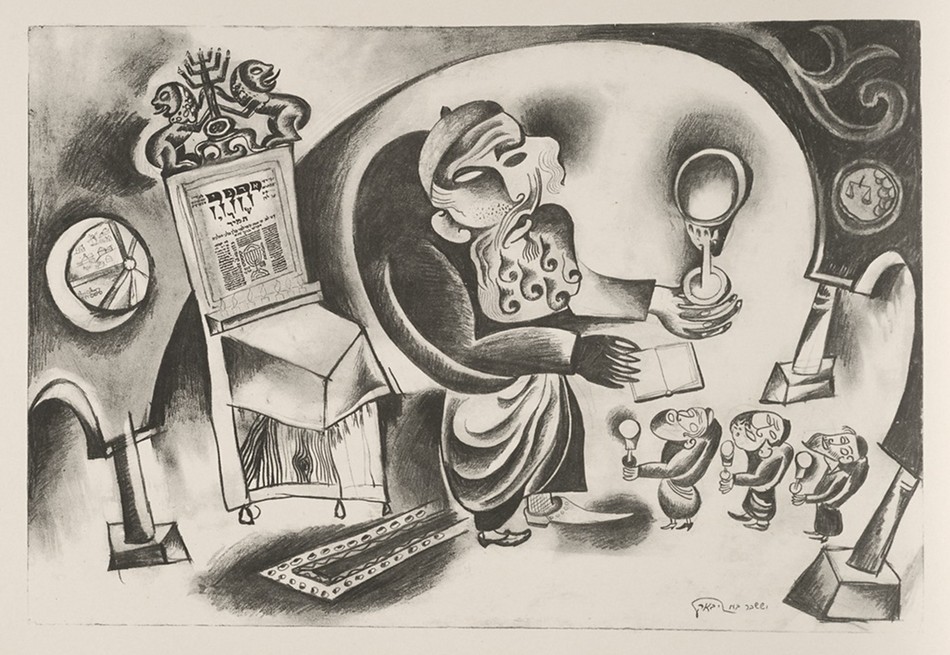

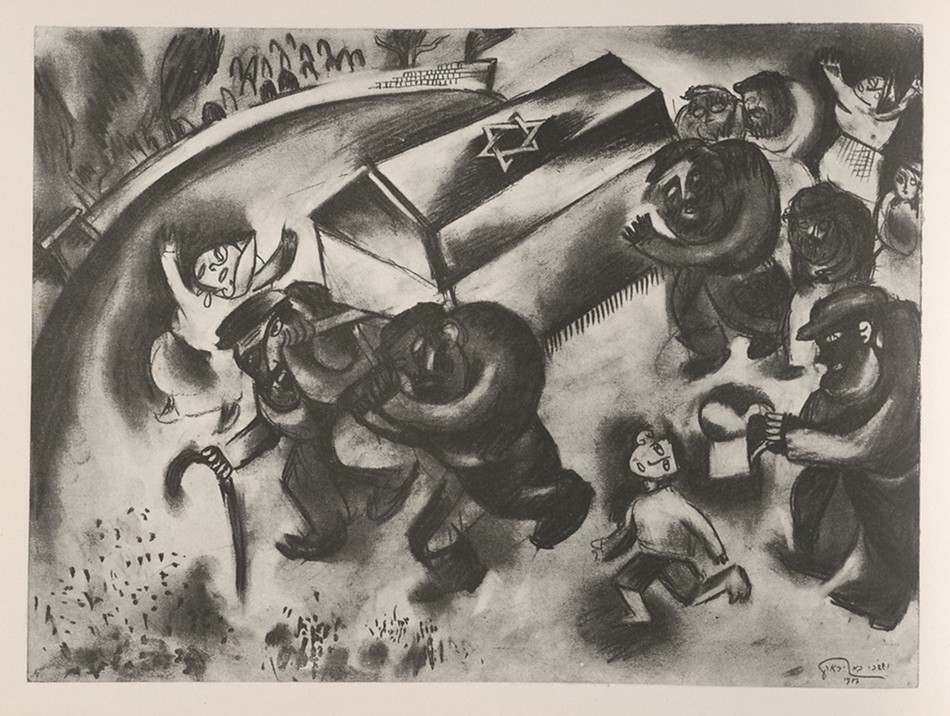

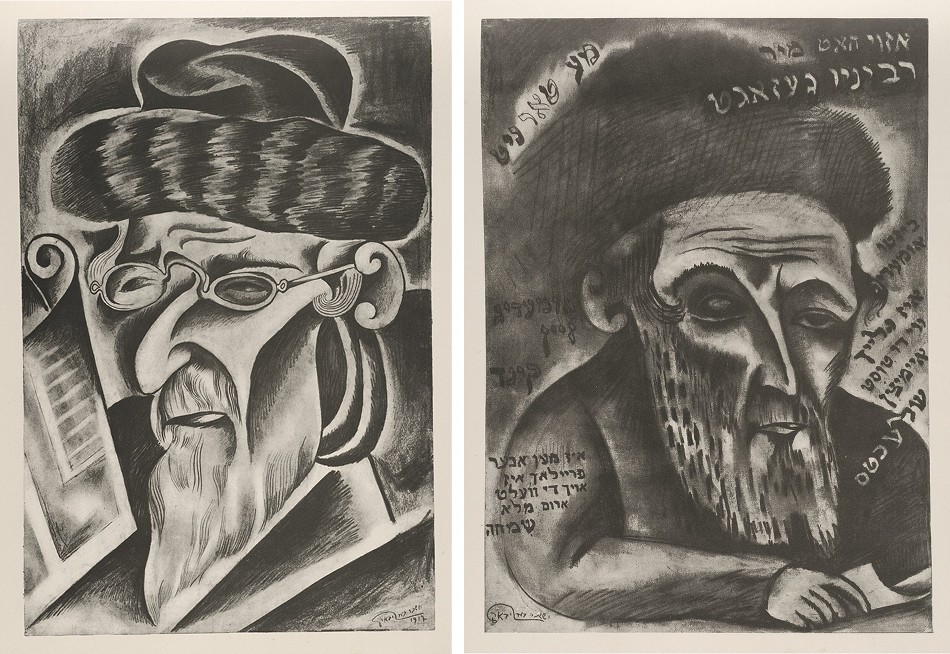

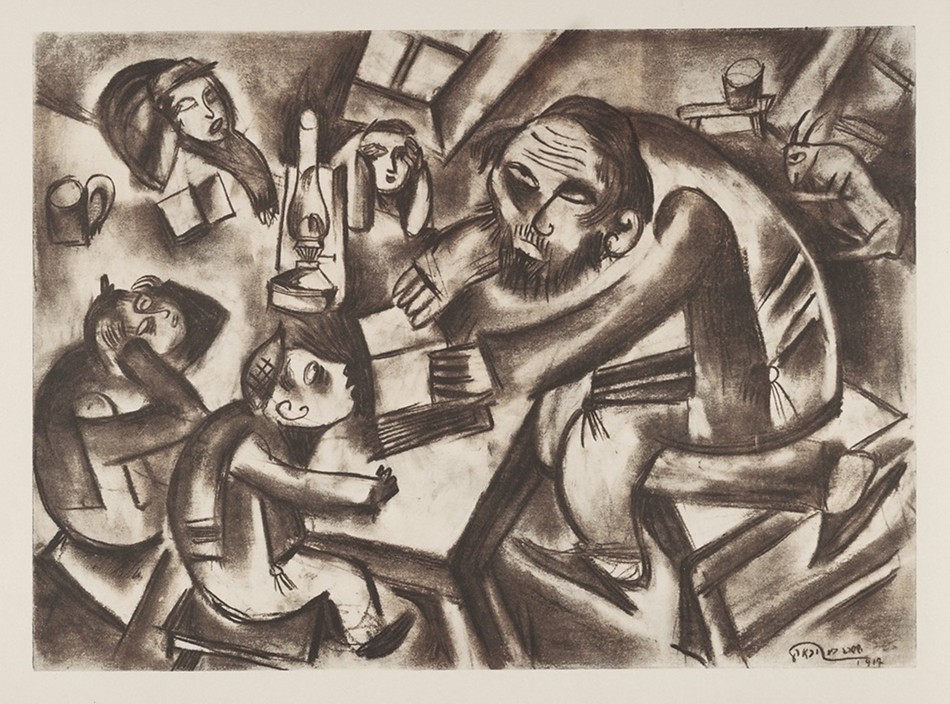

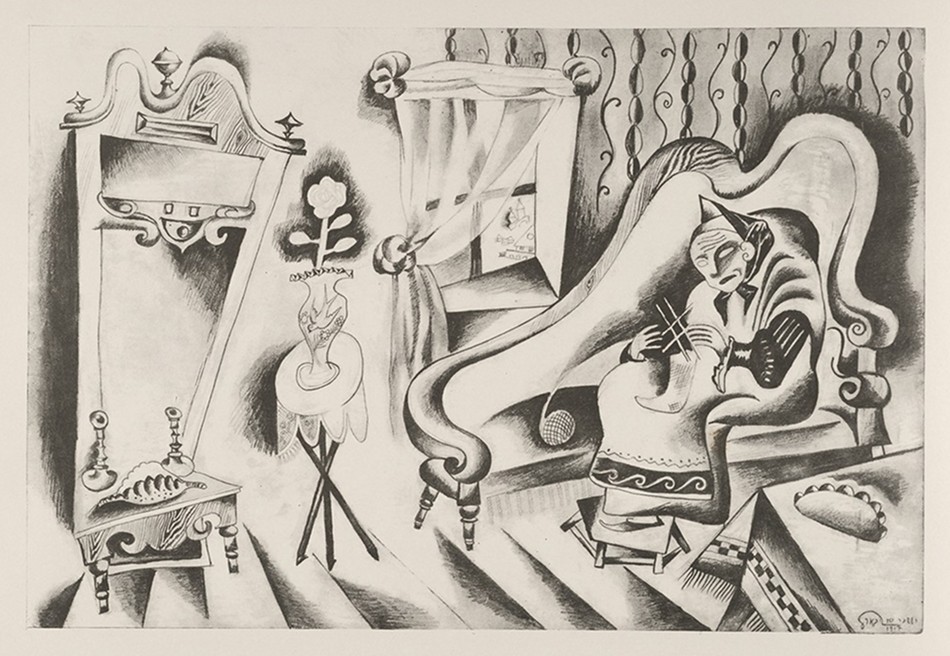

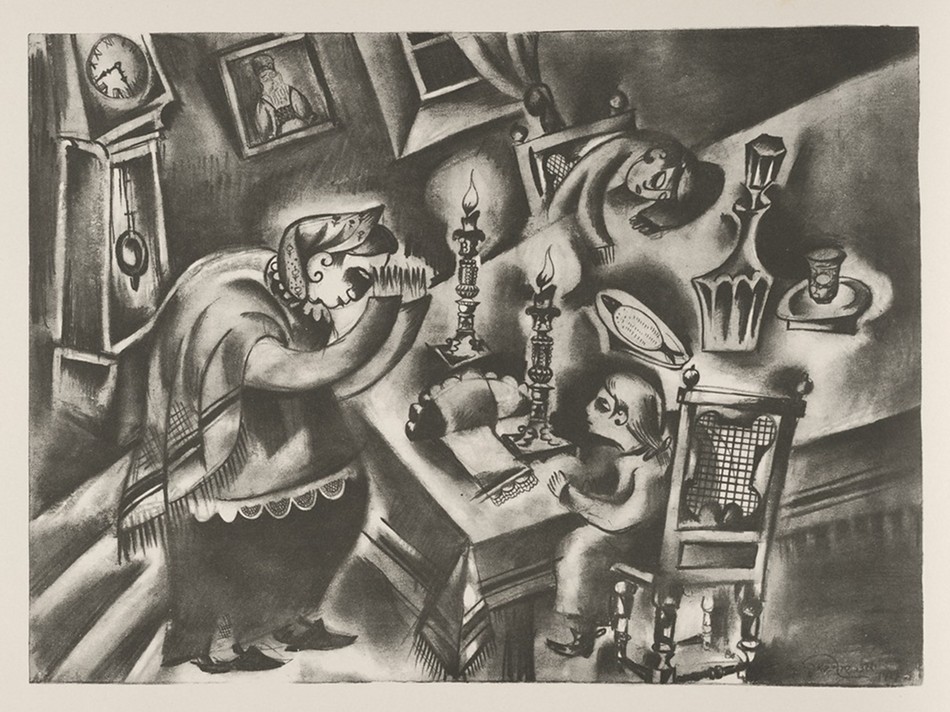

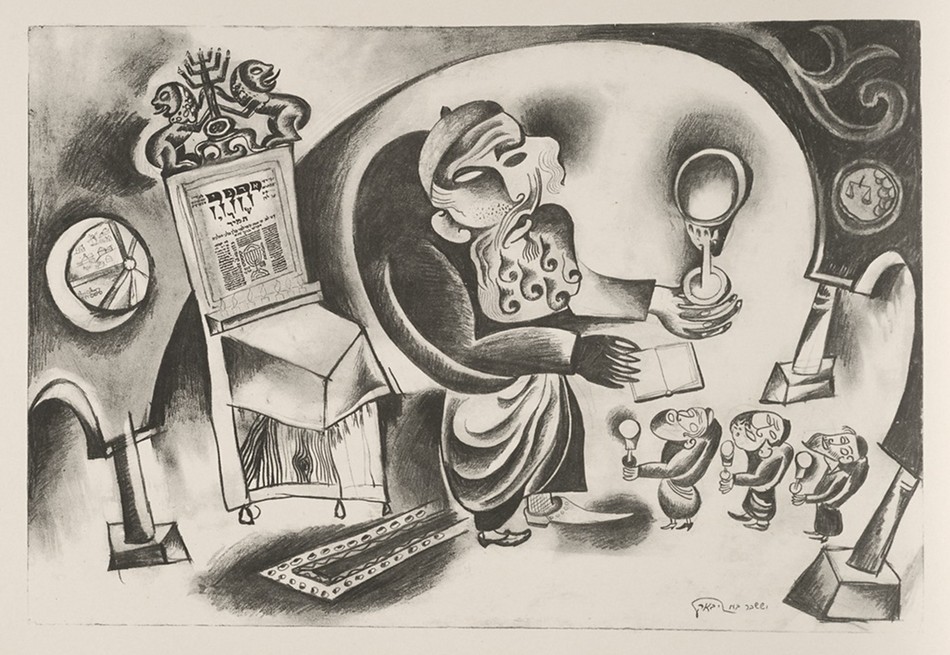

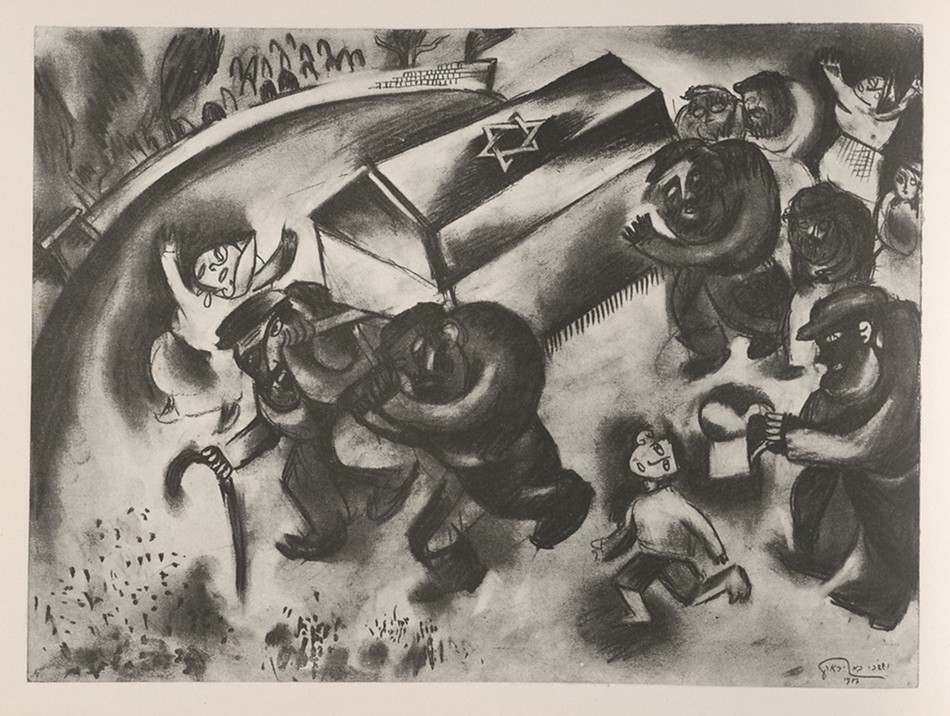

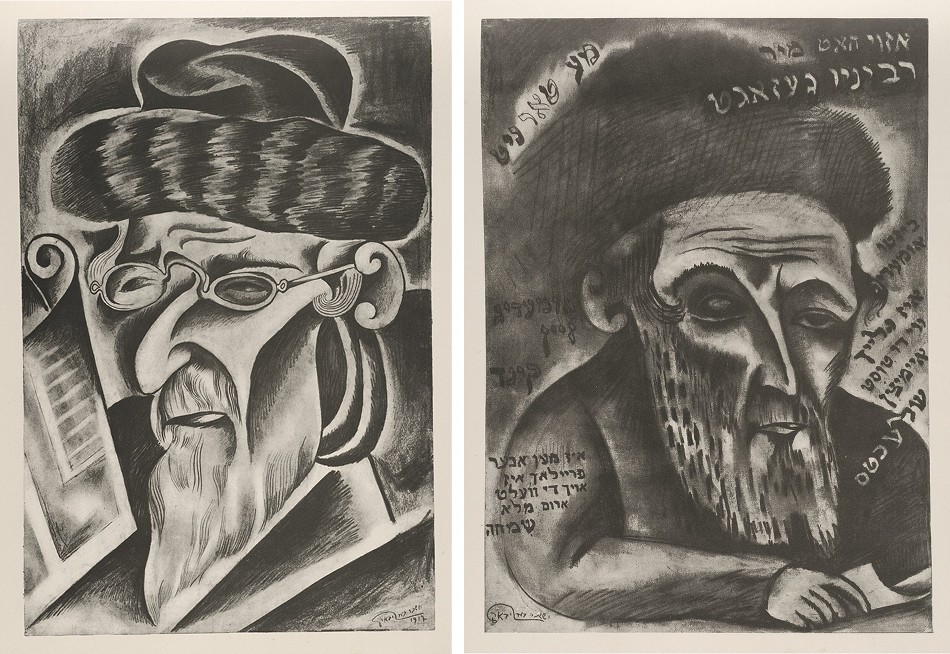

Shtetl, My Destroyed Home: A Remembrance (1922)

(From The Public Domian Review)

Shtetl, My Destroyed Home: A Remembrance (1922)

A selection from a set of 30 lithographs by the Russian artist Issachar Ber Ryback, dating mostly from 1917 and published in a book by the Berlin-based “Farlag Shveln”. The images depict scenes of Ryback’s home village in Ukraine before it was destroyed in the pogroms following World War I, a fate which seems ominously echoed in the torturous angles and distortions of form in which he represents the daily activities of village life. After graduating from art school in Kiev in 1916, Ryback played a key role in the Yiddish avant-garde of the Soviet Union following the Russian Revolution. After his father was murdered by Petliura’s soldiers in 1921, he fled to Germany, settling in Berlin where he became a member of the Novembergruppe and was involved in a number of important exhibitions. After a return trip to Russia, working on a set design for a Yiddish theatre and undertaking a prolonged journey through the Jewish “kolkhozes” of Ukraine and Crimea, he moved to Paris in 1926. Here he lived at the heart of the city’s vibrant artistic life – including solo exhibitions at the Galerie aux Quatre Chemins (1928) and Galerie L’Art Contemporain (1929) – until his death in 1935.

Shtetl, My Destroyed Home: A Remembrance (1922)

A selection from a set of 30 lithographs by the Russian artist Issachar Ber Ryback, dating mostly from 1917 and published in a book by the Berlin-based “Farlag Shveln”. The images depict scenes of Ryback’s home village in Ukraine before it was destroyed in the pogroms following World War I, a fate which seems ominously echoed in the torturous angles and distortions of form in which he represents the daily activities of village life. After graduating from art school in Kiev in 1916, Ryback played a key role in the Yiddish avant-garde of the Soviet Union following the Russian Revolution. After his father was murdered by Petliura’s soldiers in 1921, he fled to Germany, settling in Berlin where he became a member of the Novembergruppe and was involved in a number of important exhibitions. After a return trip to Russia, working on a set design for a Yiddish theatre and undertaking a prolonged journey through the Jewish “kolkhozes” of Ukraine and Crimea, he moved to Paris in 1926. Here he lived at the heart of the city’s vibrant artistic life – including solo exhibitions at the Galerie aux Quatre Chemins (1928) and Galerie L’Art Contemporain (1929) – until his death in 1935.