Laughlin Phillips, 85, who left the CIA in 1964 to launch Washingtonian magazine and then spent decades helping to revive his family's venerable contemporary art museum, the Phillips Collection, died Jan. 24 at his home in Washington, Conn. He had complications from prostate cancer.

Known as "Loc," Mr. Phillips was in his 40s before he took on a leadership role at the museum. He had served in Army intelligence during World War II and spent his early career with the CIA, including stints in Saigon and Tehran, before starting Washingtonian with a friend from the clandestine agency. He sold the publication in 1979 to devote himself to the museum, which he called "a family responsibility" that had deteriorated markedly.

He came to the job with no particular qualifications other than his blood ties to the founders. He dabbled in art as a young man but said he lacked talent and passion to make a career of it. He bluntly called himself "weak on art history" and said he "did not have the collector's instinct."

But by many published accounts, Mr. Phillips's administrative skill helped guide what had been a deteriorating jewel box of a museum, housed in the family's red brick mansion at 1600 21st St. NW, into a far more financially stable position.

The museum's current director, Dorothy Kosinski, said Mr. Phillips had "figured out a new trajectory for the museum," spending years repositioning the public perception of the collection from "private, cozy, secure" into a museum that could attract and retain much-needed public and private financial support.

The Phillips Collection, which opened to the public in 1921, is widely considered the first American museum devoted to modern art. Although much smaller and less comprehensive than the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Phillips Collection developed a formidable reputation for the high quality of its 19th- and 20th-century European and American paintings.

Mr. Phillips's father, Duncan, was the heir to the Jones and Laughlin steel fortune and became one of his generation's foremost arts patrons. He established himself as a force in collecting when he paid $125,000 for Pierre-Auguste Renoir's impressionist masterpiece "Luncheon of the Boating Party" while touring Europe. At his death in 1966, he had amassed thousands of works by famous and struggling artists including Renoir, Cezanne, Van Gogh, Degas, Klee and Rothko.

His father left a $3 million endowment, which Laughlin Phillips called a "princely" sum at the time but which inflation and other costs had made insufficient to maintain the facility.

As museum director from 1979 to 1991, Mr. Phillips said he sought to transform the Phillips Collection from "an idiosyncratic, underfunded family-run museum with a superb collection of modern art into a full-fledged professional institution."

As museum director from 1979 to 1991, Mr. Phillips said he sought to transform the Phillips Collection from "an idiosyncratic, underfunded family-run museum with a superb collection of modern art into a full-fledged professional institution."

Mr. Phillips, who served as board chairman from 1966 to 2001, supervised multi-million-dollar fundraising campaigns, starting charging admission, established corporate and personal membership programs, and sought arts endowment grants that the museum had seldom if ever pursued.

The museum professionalized its staff, at one point hiring the renowned art historian Sir Lawrence Gowing as chairman of the curatorial department. In 1989, the museum opened its $7.8 million Goh exhibition and storage space annex -- named after the Japanese industrial and his wife who were the project's leading donors.

Moreover, Mr. Phillips took steps to end the museum's casual approach to art cataloguing and conservation, having been appalled many years previously to find some pieces of art being stored in restrooms and closets. He made sure proper humidity control was installed, one of many crucial steps need to maintain art treasures in a building that dated to 1898.

The big job I faced was to gradually upgrade everything without changing the spirit of the place," Mr. Phillips told Washingtonian in 1999. "We had to take a lovable old house and create what we think of as a full-fledged professional museum."

Laughlin Phillips was born in Washington on Oct. 20, 1924. He was 6 when the family moved from its downtown manse to an 18-acre estate on Foxhall Road Northwest designed by celebrated architect John Russell Pope. The Phillipses' Foxhall home became a noted salon where the family entertained diplomats, politicians, opinion makers and artists.

At the same time, Laughlin Phillips described a protective upbringing.

His only sibling, Mary Marjorie, spent much of her life in institutions after having contracted encephalitis as a toddler. "She was severely brain damaged and never got beyond being four years old," he told Washingtonian. "Mother spent endless hours with her, believing she would get well."

Mr. Phillips was chauffeured each day from home to the private St. Albans School. After graduation in 1942, he attended Yale University for a year before serving in the Pacific during World War II and earning the Bronze Star Medal. He chose not to return to Yale, his father's alma mater, and instead enrolled at the University of Chicago on the GI Bill. He joined the CIA soon after obtaining a master's degree in philosophy.

During this period, he married Elizabeth Hood, and they had two children before divorcing. Mr. Phillips later married Jennifer Stats Cafritz, the former wife of Conrad Cafritz of the Washington real-estate family. The Phillipses moved a few years ago to Connecticut from the District.

Besides his wife, survivors include two children from his first marriage, Duncan V. Phillips of San Francisco and Liza Phillips of Narrowsburg, N.Y.; four stepchildren, Julia Cafritz and Daisy von Furth, both of Northampton, Mass., Eric Cafritz of Paris and Matthew Cafritz of the District; and 15 grandchildren.

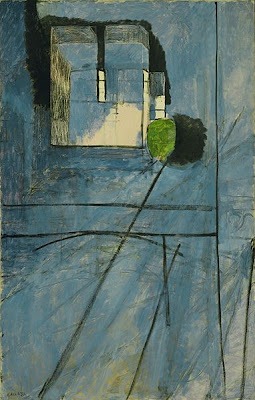

Under Laughlin Phillips's oversight, the museum expanded its library and archives and made several key purchases for its collection, including works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard, Jackson Pollock and Morris Louis.

At times, Mr. Phillips was forced to make difficult decisions about selling a prized work of art to keep the museum functioning. Washington Post art critic Paul Richard wrote witheringly of Mr. Phillips's decision to place Georges Braque's cubist painting "Music" (1914) up for auction in 1987. The work fetched $3 million.

Mr. Phillips answered that his father had often been willing to sell works of art to sustain the larger museum. "The museum's character has always had an innovative element," he once said. "It can't be sealed and preserved."